Biology of mosquitoes

There are currently 51 species of mosquitoes (Culicinae) in Germany (including two exotic mosquitoes such as the Asian bush mosquito (Aedes japonicus) and the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus)). The most important mosquito species in Germany can be roughly classified as follows:

- The so-called flood mosquitoes (genus Aedes)

- The Culex and Culiseta mosquitoes, the best known species are Culex pipiens (the common house mosquito) and Culiseta annulata (the large ring mosquito)

- The fever mosquitoes (Anopheles species), which used to transmit human malaria in Germany

- The waterbed mosquitoes (Coquillettidia richiardii), which mostly occur on lakes surrounded by reeds

General information on the biology of mosquitoes

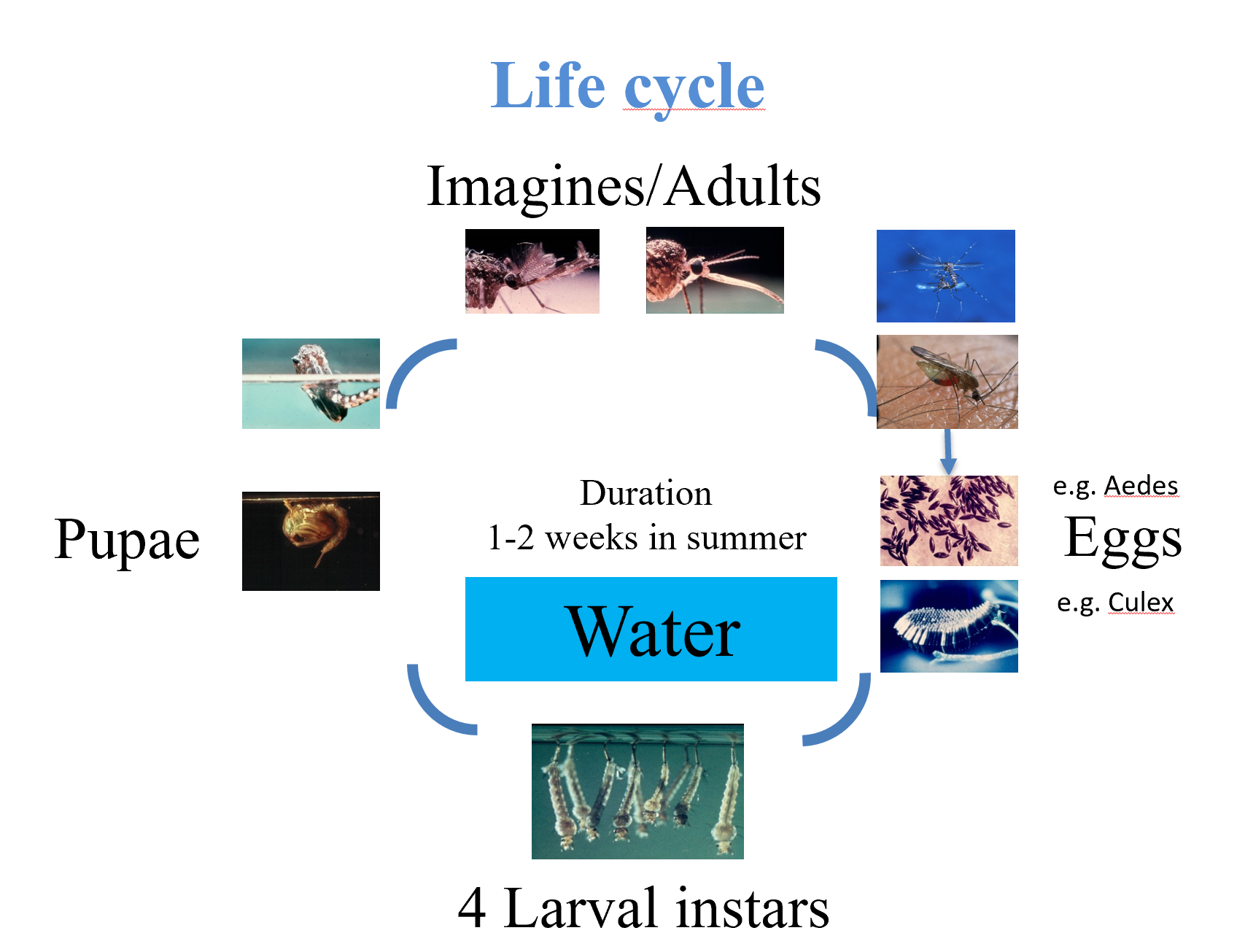

All mosquitoes depend on standing water for their development. Basically, almost any standing body of water, with little or heavy organic pollution, can be used as a breeding ground. This includes temporary flood waters along rivers and lakes or ponds and pools rich in plants, but also many small and tiny bodies of water, such as water barrels, water-filled flower vases, drains, cesspools, old tires, tree hollows or splash holes. In the body of water, the mosquitoes develop through four larval stages and a pupal stage to become flying insects. Development in water depends on temperature; higher temperatures accelerate development.

What all mosquitoes (often called "gnats") have in common is the possession of a proboscis, through which the mosquitoes can easily separate themselves from similar-looking but harmless two-winged insects, such as: B. allow the chironomid to be distinguished.

However, only the proboscis of the female mosquito is equipped with functional stinging bristles and is therefore suitable for sucking blood from humans, mammals or birds. The blood meal is necessary for the eggs to mature and thus successfully produce offspring. The male mosquitoes also have a proboscis, but this only serves to take in exposed liquids, such as sugary plant juices (nectar), as food. So only the female mosquitoes bite. They can also feed on sugary liquids, but without then forming eggs.

The female mosquito's stinging proboscis consists of six stinging bristles and the lower lip. During the blood meal, only the stinging bristles are pierced into the skin. First, the female mosquitoes are attracted to their host by chemical stimuli, especially odors, such as: B. the carbon dioxide in the air we breathe and sweat with its ingredients (butyric acid, amino acids and nitrogen compounds). At a closer distance, the temperature radiation and the moisture release of the host body are also perceived. To a lesser extent, optical stimuli (recording the host's movement in the area) also play a role, but contrary to popular belief, bright light is more repelling than attracting mosquitoes. The female mosquito flying towards a host sits on the skin and first touches the surface of the skin with the tip of the lower lip, on which a number of sensory hairs are located. With the sensory hairs that respond to temperature, smell, taste and touch stimuli, the mosquito recognizes blood vessels running under the skin, which generate an increased skin surface temperature at this point. The mosquito bites there, but often only finds a blood capillary after several attempts.

When a mosquito bites, a saliva secretion is released through a channel in a bristle. This secretion contains proteins that inhibit blood clotting, for example, and histamine, which causes a small inflammation. Pathogens contained in the saliva secretion can be transmitted when the mosquito bites, particularly in the tropics. The mosquito uses a pumping device in the area of the front digestive system to suck blood into its intestines through a channel in the upper lip until the intestines are so full that the mosquito's abdomen swells up extremely from the blood it has absorbed and turns red.

The mosquito then pulls out the stinging bristles and often flies away with difficulty due to their heavy weight. It then uses the protein-rich blood food to further develop its eggs. The biting process usually lasts around 2 minutes, sometimes longer. The mosquito takes in around twice its body weight in blood (2-3µl).

Egg laying

There are sometimes considerable differences between the different mosquito species in the way they lay their eggs and in the way they look. The native flood mosquitoes (Aedes/Ochlerotatus species) lay their eggs individually in moist soil. With a length of just under a millimeter and a diameter of around 0.3 mm, they are just barely visible to the naked eye on a white background. The eggs are heavier than water and do not float. The larvae can only hatch when the eggs are submerged by flooding or heavy rain. By developing in floodwaters that only contain water for a short time, the larvae evade the fish, who are effective predators and cannot find a habitat in the temporary waters.

The females of the genera Culex, Culiseta, and Coquillettidia glue their eggs together to form so-called “egg boats” directly on the surface of the water. A Culex pipiens clutch usually contains more than 300 eggs and is over 5 mm long and 2-3 mm wide. The egg boat of Culiseta annulata looks similar, but its eggs are slightly larger. After one to two days of embryonic development, the larvae hatch directly into the water body.

The Anopheles females lay their eggs individually on the water surface by releasing the eggs one by one above the water surface.b. Equipped with swimming chambers, the eggs float on the water surface until the larvae hatch.

Mosquito larvae/pupae

Mosquito larvae:

The body of the mosquito larvae consists of a head with eyes, antennae and mouthparts, as well as 3 fused thorax and 9 abdominal segments. In Aedes, Ochlerotatus, Culex and Culiseta, there is a strong breathing tube on the 8th abdominal segment, which the larvae use to hang on the water surface to breathe.

The larvae of the Anopheles species do not have a breathing tube; their breathing openings lie flat as a "breathing plate" directly on the back of the 8th abdominal segment. Due to the formation of this breathing plate and fan-like branching hairs all over the body (palm leaf hairs), the Anopheles larvae lie horizontally on the water surface. Due to their horizontal position, the Anopheles larvae can largely escape the reach of the fish, whereas the larvae of the genera Aedes, Culex and Culiseta hang on the surface of the water with their breathing tube so that their head and body point diagonally downwards.

The breathing tube of the larvae of the aquatic mosquito Coquillettidia richiardii differs greatly from the original shape because it has a special sawing device for drilling into plant tissue.

Mosquito pupae:

The head and chest of the pupae have grown together to form a more or less pear-shaped complex in which the limbs of the future flying insect, such as wings, legs, antennae and proboscis, develop, embedded in sheaths.

The pupa stores air under the wing and leg sheaths, so that, unlike the larvae, it is lighter than water and usually hangs on the water surface. Two respiratory sacs serve as respiratory organs and for attaching to the water surface. There is a pre-formed seam between the respiratory sacs in the middle of the front body, which bursts open when the future flying insect hatches from the pupa.

The long, narrow rump with 8 abdominal segments and two leaf-shaped appendages, called rudders, is placed on the underside of the forebody when at rest.

When the water surface is disturbed, the pupa strikes with its abdomen and oar plates and flees into the depths, only to then slowly rise back to the water surface due to the air deposits.

Unlike the larvae, the pupa no longer takes in food, as the future flying insect develops inside it. This means that pupae cannot be killed with a toxic feeding substance (e.g. with Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis (BTI) preparations) like the larvae.